Tuning Checkpoints and Large State

This page gives a guide how to configure and tune applications that use large state.

- Overview

- Monitoring State and Checkpoints

- Tuning Checkpointing

- Tuning RocksDB

- Capacity Planning

- Compression

- Task-Local Recovery

Overview

For Flink applications to run reliably at large scale, two conditions must be fulfilled:

-

The application needs to be able to take checkpoints reliably

-

The resources need to be sufficient catch up with the input data streams after a failure

The first sections discuss how to get well performing checkpoints at scale. The last section explains some best practices concerning planning how many resources to use.

Monitoring State and Checkpoints

The easiest way to monitor checkpoint behavior is via the UI’s checkpoint section. The documentation for checkpoint monitoring shows how to access the available checkpoint metrics.

The two numbers that are of particular interest when scaling up checkpoints are:

-

The time until operators start their checkpoint: This time is currently not exposed directly, but corresponds to:

checkpoint_start_delay = end_to_end_duration - synchronous_duration - asynchronous_durationWhen the time to trigger the checkpoint is constantly very high, it means that the checkpoint barriers need a long time to travel from the source to the operators. That typically indicates that the system is operating under a constant backpressure.

-

The amount of data buffered during alignments. For exactly-once semantics, Flink aligns the streams at operators that receive multiple input streams, buffering some data for that alignment. The buffered data volume is ideally low - higher amounts means that checkpoint barriers are received at very different times from the different input streams.

Note that when the here indicated numbers can be occasionally high in the presence of transient backpressure, data skew, or network issues. However, if the numbers are constantly very high, it means that Flink puts many resources into checkpointing.

Tuning Checkpointing

Checkpoints are triggered at regular intervals that applications can configure. When a checkpoint takes longer to complete than the checkpoint interval, the next checkpoint is not triggered before the in-progress checkpoint completes. By default the next checkpoint will then be triggered immediately once the ongoing checkpoint completes.

When checkpoints end up frequently taking longer than the base interval (for example because state grew larger than planned, or the storage where checkpoints are stored is temporarily slow), the system is constantly taking checkpoints (new ones are started immediately once ongoing once finish). That can mean that too many resources are constantly tied up in checkpointing and that the operators make too little progress. This behavior has less impact on streaming applications that use asynchronously checkpointed state, but may still have an impact on overall application performance.

To prevent such a situation, applications can define a minimum duration between checkpoints:

StreamExecutionEnvironment.getCheckpointConfig().setMinPauseBetweenCheckpoints(milliseconds)

This duration is the minimum time interval that must pass between the end of the latest checkpoint and the beginning of the next. The figure below illustrates how this impacts checkpointing.

Note: Applications can be configured (via the CheckpointConfig) to allow multiple checkpoints to be in progress at

the same time. For applications with large state in Flink, this often ties up too many resources into the checkpointing.

When a savepoint is manually triggered, it may be in process concurrently with an ongoing checkpoint.

Tuning RocksDB

The state storage workhorse of many large scale Flink streaming applications is the RocksDB State Backend. The backend scales well beyond main memory and reliably stores large keyed state.

RocksDB’s performance can vary with configuration, this section outlines some best-practices for tuning jobs that use the RocksDB State Backend.

Incremental Checkpoints

When it comes to reducing the time that checkpoints take, activating incremental checkpoints should be one of the first considerations. Incremental checkpoints can dramatically reduce the checkpointing time in comparison to full checkpoints, because incremental checkpoints only record the changes compared to the previous completed checkpoint, instead of producing a full, self-contained backup of the state backend.

See Incremental Checkpoints in RocksDB for more background information.

Timers in RocksDB or on JVM Heap

Timers are stored in RocksDB by default, which is the more robust and scalable choice.

When performance-tuning jobs that have few timers only (no windows, not using timers in ProcessFunction), putting those timers on the heap can increase performance. Use this feature carefully, as heap-based timers may increase checkpointing times and naturally cannot scale beyond memory.

See this section for details on how to configure heap-based timers.

Tuning RocksDB Memory

The performance of the RocksDB State Backend much depends on the amount of memory that it has available. To increase performance, adding memory can help a lot, or adjusting to which functions memory goes.

By default, the RocksDB State Backend uses Flink’s managed memory budget for RocksDBs buffers and caches (state.backend.rocksdb.memory.managed: true). Please refer to the RocksDB Memory Management for background on how that mechanism works.

To tune memory-related performance issues, the following steps may be helpful:

-

The first step to try and increase performance should be to increase the amount of managed memory. This usually improves the situation a lot, without opening up the complexity of tuning low-level RocksDB options.

Especially with large container/process sizes, much of the total memory can typically go to RocksDB, unless the application logic requires a lot of JVM heap itself. The default managed memory fraction (0.4) is conservative and can often be increased when using TaskManagers with multi-GB process sizes.

-

The number of write buffers in RocksDB depends on the number of states you have in your application (states across all operators in the pipeline). Each state corresponds to one ColumnFamily, which needs its own write buffers. Hence, applications with many states typically need more memory for the same performance.

-

You can try and compare the performance of RocksDB with managed memory to RocksDB with per-column-family memory by setting

state.backend.rocksdb.memory.managed: false. Especially to test against a baseline (assuming no- or gracious container memory limits) or to test for regressions compared to earlier versions of Flink, this can be useful.Compared to the managed memory setup (constant memory pool), not using managed memory means that RocksDB allocates memory proportional to the number of states in the application (memory footprint changes with application changes). As a rule of thumb, the non-managed mode has (unless ColumnFamily options are applied) an upper bound of roughly “140MB * num-states-across-all-tasks * num-slots”. Timers count as state as well!

-

If your application has many states and you see frequent MemTable flushes (write-side bottleneck), but you cannot give more memory you can increase the ratio of memory going to the write buffers (

state.backend.rocksdb.memory.write-buffer-ratio). See RocksDB Memory Management for details. -

An advanced option (expert mode) to reduce the number of MemTable flushes in setups with many states, is to tune RocksDB’s ColumnFamily options (arena block size, max background flush threads, etc.) via a

RocksDBOptionsFactory:

public class MyOptionsFactory implements ConfigurableRocksDBOptionsFactory {

@Override

public DBOptions createDBOptions(DBOptions currentOptions, Collection<AutoCloseable> handlesToClose) {

// increase the max background flush threads when we have many states in one operator,

// which means we would have many column families in one DB instance.

return currentOptions.setMaxBackgroundFlushes(4);

}

@Override

public ColumnFamilyOptions createColumnOptions(

ColumnFamilyOptions currentOptions, Collection<AutoCloseable> handlesToClose) {

// decrease the arena block size from default 8MB to 1MB.

return currentOptions.setArenaBlockSize(1024 * 1024);

}

@Override

public OptionsFactory configure(Configuration configuration) {

return this;

}

}Capacity Planning

This section discusses how to decide how many resources should be used for a Flink job to run reliably. The basic rules of thumb for capacity planning are:

-

Normal operation should have enough capacity to not operate under constant back pressure. See back pressure monitoring for details on how to check whether the application runs under back pressure.

-

Provision some extra resources on top of the resources needed to run the program back-pressure-free during failure-free time. These resources are needed to “catch up” with the input data that accumulated during the time the application was recovering. How much that should be depends on how long recovery operations usually take (which depends on the size of the state that needs to be loaded into the new TaskManagers on a failover) and how fast the scenario requires failures to recover.

Important: The base line should to be established with checkpointing activated, because checkpointing ties up some amount of resources (such as network bandwidth).

-

Temporary back pressure is usually okay, and an essential part of execution flow control during load spikes, during catch-up phases, or when external systems (that are written to in a sink) exhibit temporary slowdown.

-

Certain operations (like large windows) result in a spiky load for their downstream operators: In the case of windows, the downstream operators may have little to do while the window is being built, and have a load to do when the windows are emitted. The planning for the downstream parallelism needs to take into account how much the windows emit and how fast such a spike needs to be processed.

Important: In order to allow for adding resources later, make sure to set the maximum parallelism of the data stream program to a reasonable number. The maximum parallelism defines how high you can set the programs parallelism when re-scaling the program (via a savepoint).

Flink’s internal bookkeeping tracks parallel state in the granularity of max-parallelism-many key groups. Flink’s design strives to make it efficient to have a very high value for the maximum parallelism, even if executing the program with a low parallelism.

Compression

Flink offers optional compression (default: off) for all checkpoints and savepoints. Currently, compression always uses the snappy compression algorithm (version 1.1.4) but we are planning to support custom compression algorithms in the future. Compression works on the granularity of key-groups in keyed state, i.e. each key-group can be decompressed individually, which is important for rescaling.

Compression can be activated through the ExecutionConfig:

ExecutionConfig executionConfig = new ExecutionConfig();

executionConfig.setUseSnapshotCompression(true);Note The compression option has no impact on incremental snapshots, because they are using RocksDB’s internal format which is always using snappy compression out of the box.

Task-Local Recovery

Motivation

In Flink’s checkpointing, each task produces a snapshot of its state that is then written to a distributed store. Each task acknowledges a successful write of the state to the job manager by sending a handle that describes the location of the state in the distributed store. The job manager, in turn, collects the handles from all tasks and bundles them into a checkpoint object.

In case of recovery, the job manager opens the latest checkpoint object and sends the handles back to the corresponding tasks, which can then restore their state from the distributed storage. Using a distributed storage to store state has two important advantages. First, the storage is fault tolerant and second, all state in the distributed store is accessible to all nodes and can be easily redistributed (e.g. for rescaling).

However, using a remote distributed store has also one big disadvantage: all tasks must read their state from a remote location, over the network. In many scenarios, recovery could reschedule failed tasks to the same task manager as in the previous run (of course there are exceptions like machine failures), but we still have to read remote state. This can result in long recovery time for large states, even if there was only a small failure on a single machine.

Approach

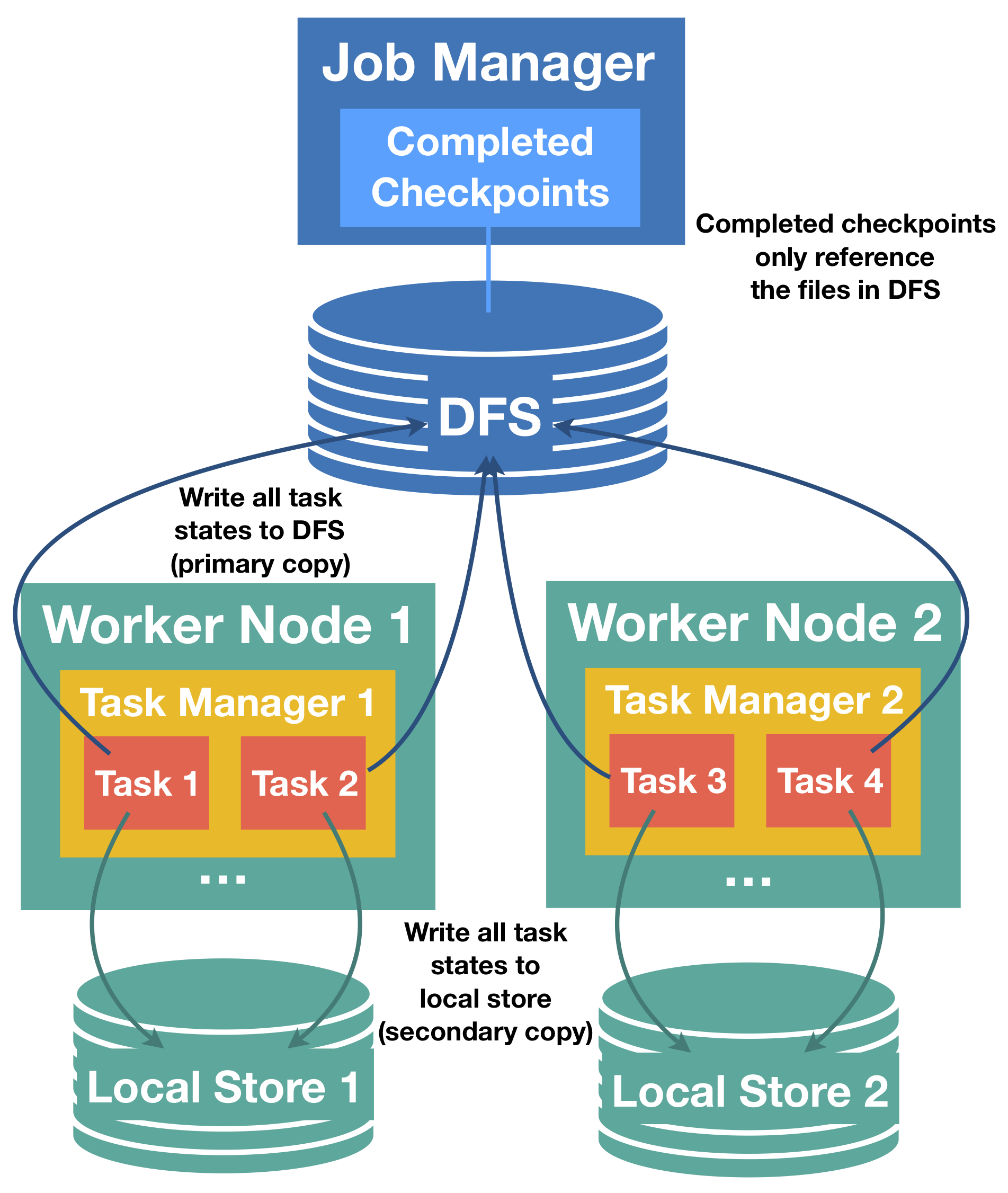

Task-local state recovery targets exactly this problem of long recovery time and the main idea is the following: for every checkpoint, each task does not only write task states to the distributed storage, but also keep a secondary copy of the state snapshot in a storage that is local to the task (e.g. on local disk or in memory). Notice that the primary store for snapshots must still be the distributed store, because local storage does not ensure durability under node failures and also does not provide access for other nodes to redistribute state, this functionality still requires the primary copy.

However, for each task that can be rescheduled to the previous location for recovery, we can restore state from the secondary, local copy and avoid the costs of reading the state remotely. Given that many failures are not node failures and node failures typically only affect one or very few nodes at a time, it is very likely that in a recovery most tasks can return to their previous location and find their local state intact. This is what makes local recovery effective in reducing recovery time.

Please note that this can come at some additional costs per checkpoint for creating and storing the secondary local state copy, depending on the chosen state backend and checkpointing strategy. For example, in most cases the implementation will simply duplicate the writes to the distributed store to a local file.

Relationship of primary (distributed store) and secondary (task-local) state snapshots

Task-local state is always considered a secondary copy, the ground truth of the checkpoint state is the primary copy in the distributed store. This has implications for problems with local state during checkpointing and recovery:

-

For checkpointing, the primary copy must be successful and a failure to produce the secondary, local copy will not fail the checkpoint. A checkpoint will fail if the primary copy could not be created, even if the secondary copy was successfully created.

-

Only the primary copy is acknowledged and managed by the job manager, secondary copies are owned by task managers and their life cycles can be independent from their primary copies. For example, it is possible to retain a history of the 3 latest checkpoints as primary copies and only keep the task-local state of the latest checkpoint.

-

For recovery, Flink will always attempt to restore from task-local state first, if a matching secondary copy is available. If any problem occurs during the recovery from the secondary copy, Flink will transparently retry to recover the task from the primary copy. Recovery only fails, if primary and the (optional) secondary copy failed. In this case, depending on the configuration Flink could still fall back to an older checkpoint.

-

It is possible that the task-local copy contains only parts of the full task state (e.g. exception while writing one local file). In this case, Flink will first try to recover local parts locally, non-local state is restored from the primary copy. Primary state must always be complete and is a superset of the task-local state.

-

Task-local state can have a different format than the primary state, they are not required to be byte identical. For example, it could be even possible that the task-local state is an in-memory consisting of heap objects, and not stored in any files.

-

If a task manager is lost, the local state from all its task is lost.

Configuring task-local recovery

Task-local recovery is deactivated by default and can be activated through Flink’s configuration with the key state.backend.local-recovery as specified

in CheckpointingOptions.LOCAL_RECOVERY. The value for this setting can either be true to enable or false (default) to disable local recovery.

Note that unaligned checkpoints currently do not support task-local recovery.

Details on task-local recovery for different state backends

Limitation: Currently, task-local recovery only covers keyed state backends. Keyed state is typically by far the largest part of the state. In the near future, we will also cover operator state and timers.

The following state backends can support task-local recovery.

-

FsStateBackend: task-local recovery is supported for keyed state. The implementation will duplicate the state to a local file. This can introduce additional write costs and occupy local disk space. In the future, we might also offer an implementation that keeps task-local state in memory.

-

RocksDBStateBackend: task-local recovery is supported for keyed state. For full checkpoints, state is duplicated to a local file. This can introduce additional write costs and occupy local disk space. For incremental snapshots, the local state is based on RocksDB’s native checkpointing mechanism. This mechanism is also used as the first step to create the primary copy, which means that in this case no additional cost is introduced for creating the secondary copy. We simply keep the native checkpoint directory around instead of deleting it after uploading to the distributed store. This local copy can share active files with the working directory of RocksDB (via hard links), so for active files also no additional disk space is consumed for task-local recovery with incremental snapshots. Using hard links also means that the RocksDB directories must be on the same physical device as all the configure local recovery directories that can be used to store local state, or else establishing hard links can fail (see FLINK-10954). Currently, this also prevents using local recovery when RocksDB directories are configured to be located on more than one physical device.

Allocation-preserving scheduling

Task-local recovery assumes allocation-preserving task scheduling under failures, which works as follows. Each task remembers its previous allocation and requests the exact same slot to restart in recovery. If this slot is not available, the task will request a new, fresh slot from the resource manager. This way, if a task manager is no longer available, a task that cannot return to its previous location will not drive other recovering tasks out of their previous slots. Our reasoning is that the previous slot can only disappear when a task manager is no longer available, and in this case some tasks have to request a new slot anyways. With our scheduling strategy we give the maximum number of tasks a chance to recover from their local state and avoid the cascading effect of tasks stealing their previous slots from one another.